This Is Not A

BLOG!

This Is Not A

BLOG!

Date: 27/11/19

"The Tombstone Of My Enemy Has Been Vandalised"

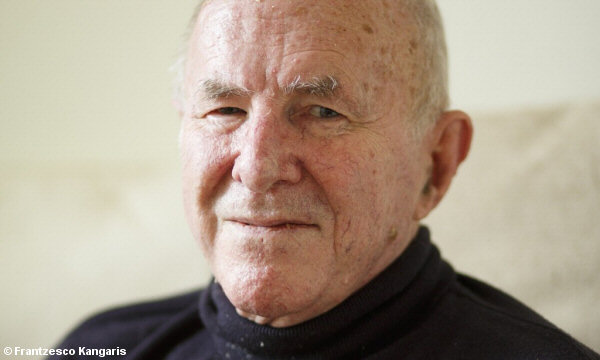

Clive (né Vivian) Leopold James

Author, critic, broadcaster, poet

b. 7 October 1939, d. 24 November 2019

Anyone with any degree of cultural awareness will have come across some aspect or another of the work of Clive James.

From the heights of criticism for an array of reputable journals, via his verse (both light and serious), through his televsion documentaries and to the shows which introduced us to the dizzyingly varied delights of Sylvester Stallone's mother, Margarita Pracatan and the sight of Japanese game-show contestants having boiling oil (or something equally humiliating) poured over them, he filled just about every niche there was to inhabit in popular culture (in the same way that his friend Jonathan Miller - whose death was announced on the same day as James' was - did much the same in more exalted realms of artistic endeavour).

I think I first encountered him on television in the late 1970s, when - alongside Russell Harty and Janet Street-Porter - he presented the late-night end-of-the-week chat show Saturday Night People for ITV, in the days when the commercial broadcaster was willing to look slightly radical once in a while.

But my real introduction to the man and his style came from borrowing from Wrexham Library his collections of television criticism first published in the Observer between 1972 and 1982. Everyone knows about his ability to create arresting - if unsettling - images in words of some performer or another: describing Schwarzenegger (in his body-builder days) as looking like a condom full of walnuts, say; or the ridiculous North Face of Barbara Cartland as resembling a chalk cliff into which two crows had crashed. But he could also be warm towards genuine battiness, as he was when describing the dog-trainer Barbara Woodhouse, whose apparent eccentricities he perceived as utterly authentic.

He could just as often be ascerbic, however: his full-on disgust at the way in which old Nazis (such as Albert Speer) and their followers (such as Oswald Mosley) were given air-time to try to justify their conduct or ingratiate themselves with the public came under James' relentless scorn; his views of the far left were no less biting, seeing it as a betrayal by unthinking obsessive ideological puritans of the slightly left-of-centre view with which he had always sympathised.

In all these modes, he was seldom less than entertaining, and could be poetic even when describing something quite ludicrous, such as a delayed space launch, where he speculated that the onboard computer - whose wayward behaviour was holding up the proceedings - was at first too busy cataloguing old 78 rpm records and then too engrossed in counting the stars.

Sensing in 1982 that he was in danger of ending up reviewing one of his own increasingly frequent appearances on the medium, he gave the job up. It is mildly interesting to speculate as to whether anyone could do it that way today, or indeed whether it would be worth anyone trying to do it at all, so etiolated has television become in our multi-choice paradise where what talent there is is spread thinner than the margarine in old Blue Band commercials.

His television career flourished thereafter, but brought some of his weaknesses to the fore. In his chat-shows at least, he seemed to be forever trying to stifle his laughter at his own jokes, and some of his running jokes went on for so long that they became winded old nags out of whose misery one hoped they would be put; one of his end-of-the-year shows had a repeated reference to 'Yasmin Arafat' which was only slightly amusing the first time, but had become as predictable as an Israeli air attack on Gaza by the end of the programme - and with much the same effect on at least one viewer.

His documentaries, however, had more depth to them (probably as a result of his having had more time to ponder over what he wanted to say), and were not without their wit; going up in a light aircraft with San Francisco 49ers' tight end Russ Francis, James commented that the experience proved to him that a tight end was something he didn't have.

His 'serious' programmes and series were well written and well presented - if sometimes with too great an element of the sententious. Being an auto-didact in most disciplines beyond the English literature he had studied at Sydney and Cambridge, he had a tendency to be a show-off with what he had gleaned from his admittedly thorough reading and to be censorious towards any political idea too far beyond the comfort zone of a white Western liberal. At his best however, with such as Fame In The 20th Century, he could succeed in pulling together apparently disparate events and people to show us a common pattern and be genuinely illuminating to the viewer.

Clive James retreated from television for much the same reason as he removed himself from writing about it; in order to prevent the whole experience becoming self-referential for the producer and the consumer of the product alike. He devoted the rest of his life to the written word (with occasional excursions into radio), to his criticism and his verse.

It has to be said that much of his 'comic' verse - especially from the 1970s - and some of the lyrics he wrote for Pete Atkin suffered then - and suffer even more so today - from the impression of having been written by a first-year undergraduate trying to please his seniors; but his deeper work - especially in later life - repays careful attention.

Although he wasn't as multivalent as Jonathan Miller, Clive James made a strong and visible impact on many areas of culture, and his best work will continue to enlighten and entertain us for as long as people wish to partake of either state.

This Is Not A

BLOG!

This Is Not A

BLOG!